What are emotions?

What a silly question! Everybody knows what emotions are - or do they?

As it turns out, emotion science has a history of arguing about what it is that it deals with. However, the situation is not so bad - over time, a consensus is emerging that involves some key aspects of what emotions, as studied by scientific research, are. In my opinion, much of the discussion and debate is of historical interest and not of practical significance. However, important emotion researchers still differ with regard to what they feel is part of emotion and what is not, what the functions of emotions are, and other aspects (see, Izard, 2010; Widen & Russell, 2010). At a recent conference, my colleague Andrea Scarantino suggested that the situation is a bit like with cooking recipe where everybody agrees on what is in it, but not the exact quantities and how things are combined.

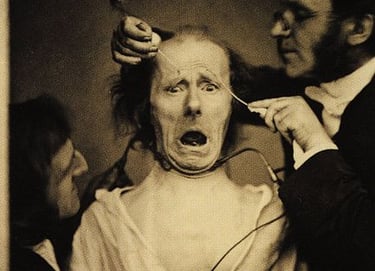

In everyday language, emotions are often seen as synonymous with feelings. However, today most scientists also consider other phenomena as part of emotions, such as changes in bodily activity, including brain activity. Some of these bodily changes can be seen, such as a blush or a smile, and others cannot, such as a change in blood pressure. Often researchers will also emphasize that emotions cause changes in action tendencies, for example, getting ready to move away or eliciting explicit actions, such as hugging someone. These different aspects of emotions are also often referred to as components of emotional reactions. Some researchers in the 20th century believed that emotions are packages or programs that would lead to very stereotypical changes, in the face, in other parts of the body, and in how we feel. However, now that much empirical research has been collected, we understand that the components are only loosely connected. When researchers try to measure emotions, they will assess more than one component.

In scientific terms, emotion is a construct. In using constructs, we give a single name to a bunch of related processes because it facilitates talking about them. Yet, when we look very closely to distinguish one construct from another, it becomes apparent that it is not easy to define the boundaries of such things clearly. This is not unique to emotion, but consider terms such as intelligence, democracy, market, family, or impressionism. Not only does it take more than a paragraph to define such a complex construct, our understanding is also always in flux as new findings appear and scientific exchanges lead to a better understanding of the phenomena we look at.

Emotion, motivation, and cognition are three psychological terms that relate in interesting ways to one another. It is not so easy to separate them in the brain based on what we have learned in the last decades of neuroscience research. It becomes essential to define such constructs when one actually wants to do something with them - for example, building artificial systems are often associated with the terms cognition and intelligence (do not get me started on that one 😊), but rarely with emotion and motivation. And yet, there is an increasing interest in implementing emotions in machines. So what does that mean? The capacity to classify nonverbal behavior in humans? Express emotions in motions and via faces and sounds? Empathy? Should machines feel something? So clearly, it is critical to be straight regarding what somebody refers to when they say that a particular system, say a robot, should have emotions. Or somebody else who says that robots could never have emotions.

In Kappas (2013) I have stated: "Emotions are evolved systems of intra- and interpersonal processes that are regulatory in nature, dealing mostly with issues of personal or social concern." - this sentence is densely packed and refers to many different aspects of the causes and consequences of emotions. If you are curious, I invite you to read the paper here.

Some take-home messages:

feelings are not emotions

emotions have biological and cultural determinants

emotions have evolutionary benefits for the species

language and culture influence how we perceive our feelings

many emotional processes are social in how they come about, how they manifest, and in their effects

References

Izard, C. E. (2010). The many meanings/aspects of emotion: Emotion definitions, functions, activation, and regulation. Emotion Review, 2, 363–370.

Kappas, A. (2013). Social regulation of emotion: Messy layers. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 51. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00051.

Widen, S.C. & Russell, J.A. (2010a). Descriptive and Prescriptive Definitions of Emotion. Emotion Review, 2, 377-378.

ChatGPT, why are psychological constructs so difficult to define?

(This summary that ChatGPT provided (30.12.2025) is not bad)

Psychological constructs are difficult to define because they sit at the intersection of abstract theory, messy human behavior, and methodological constraints. A few core reasons explain the problem:

1. They are latent, not directly observable

Most psychological constructs—intelligence, motivation, anxiety, self-control—cannot be observed in the way temperature or height can. We infer them from indicators (test scores, behaviors, self-reports), but:

Different indicators capture different aspects

Indicators are imperfect and theory-laden

Inference always leaves room for interpretation

So the construct is never “given” by the data; it is constructed by researchers.

2. They are theory-dependent

A construct’s meaning depends on the theoretical framework behind it.

“Intelligence” in a psychometric model ≠ intelligence in a cognitive model ≠ intelligence in a sociocultural model

“Emotion” in appraisal theory ≠ emotion in basic-emotion theory

Because psychology lacks a single unifying theory of mind, constructs remain plural and contested rather than fixed.

3. Ordinary language interferes

Psychological constructs often reuse everyday words (stress, memory, attention), but:

Everyday meanings are vague and context-dependent

Scientific meanings try to be precise and technical

The two constantly bleed into each other

This creates conceptual slippage between common-sense understanding and scientific usage.

4. Human behavior is context-sensitive

Psychological phenomena vary across:

Situations

Cultures

Developmental stages

Social roles

As a result, a definition that works well in one context may fail in another. Constructs must either become broad (and vague) or narrow (and incomplete).

5. Measurement feeds back into definition

In psychology, constructs are often defined by how they are measured (“operational definitions”), but this creates problems:

Measures shape what the construct becomes

Different instruments imply different constructs

Constructs risk collapsing into “whatever this test measures”

This is the classic construct validity problem.

6. They bundle heterogeneous phenomena

Many constructs are not single things but clusters:

“Depression” bundles mood, cognition, behavior, physiology

“Personality traits” summarize long-term behavioral tendencies

Such constructs trade explanatory power for simplicity, making clean definitions difficult.

7. Normativity and values creep in

Some constructs implicitly encode judgments about what is:

Normal vs. abnormal

Adaptive vs. maladaptive

Rational vs. irrational

These value-laden aspects make definitions philosophically and culturally contested, not purely empirical.

In short

Psychological constructs are difficult to define because they are abstract, theory-bound, context-sensitive, measurement-dependent, and value-laden. They are not discovered like natural kinds but negotiated within scientific communities.

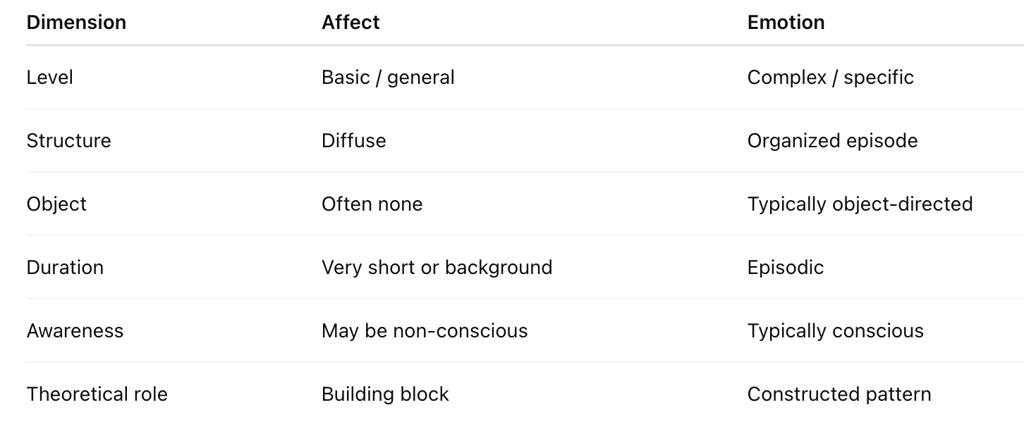

ChatGPT, what is the difference between emotion and affect?

EThe difference between emotion and affect lies mainly in level of analysis, complexity, and temporal structure. They are related but not interchangeable, and different theories draw the boundary slightly differently.

1. Affect: the broad, basic umbrella

Affect refers to the most general, primitive, and continuous feeling states.

Typical characteristics:

Valenced: pleasant ↔ unpleasant

Often includes arousal: activated ↔ deactivated

Can exist without clear object, cause, or awareness

May be conscious or non-conscious

Often short-lived and fluctuating

Examples:

Feeling “good” or “bad”

A vague sense of tension or calm

Background mood tone

Affect is frequently modeled dimensionally (e.g., valence × arousal).

2. Emotion: structured, discrete episodes

Emotions are more complex, differentiated, and episodic phenomena.

Typical characteristics:

Object-directed (“angry at someone,” “afraid of something”)

Involve appraisals (interpretations of a situation)

Include multiple components:

subjective experience

physiological changes

expressive behavior

action tendencies

Usually consciously experienced

Time-limited but longer than raw affect

Examples:

Anger, fear, joy, guilt, pride

Emotions are often treated as discrete categories, though not all theories agree.

3. Key contrasts (simplified)

4. How theories differ

Not all approaches agree on this distinction:

Basic emotion theories: Emotions are biologically hardwired; affect is a byproduct.

Dimensional theories: Affect is fundamental; emotions are interpretations of affect.

Constructionist theories (e.g., Lisa Feldman Barrett): Emotions are constructed from core affect plus conceptual knowledge.

Psychoanalytic traditions: Affect refers to raw feeling; emotion includes symbolic elaboration.

So the difference is partly conceptual, not purely empirical.

5. Why the distinction matters

Measurement: affect scales vs. emotion inventories

Theory building: dimensional vs. categorical models

Clinical practice: targeting mood tone vs. specific emotional episodes

Argumentation: debates often hinge on definitional choices, not data

In one sentence

Affect is the basic, continuous feeling dimension; emotion is a structured, meaningful episode built upon affect.